Until we measure exclusion we won’t get inclusive transport

Mon, July 26, 2021 | EquityThis article by our Principal Researcher Bridget Doran was originally posted on LinkedIn.

A recent article "Just build a ramp" got me thinking about how we provide for accessibility. The world didn't evolve with ramps and other universal design accommodations in place by default, so we relied on decades of advocacy and incremental enlightenment to develop transportation design codes that provide for inclusion.

Unfortunately for disabled people and our future selves - over half of us will be disabled by age 65 if we are fortunate enough to live that long- the world is not inclusive yet. So how can we accelerate progress?

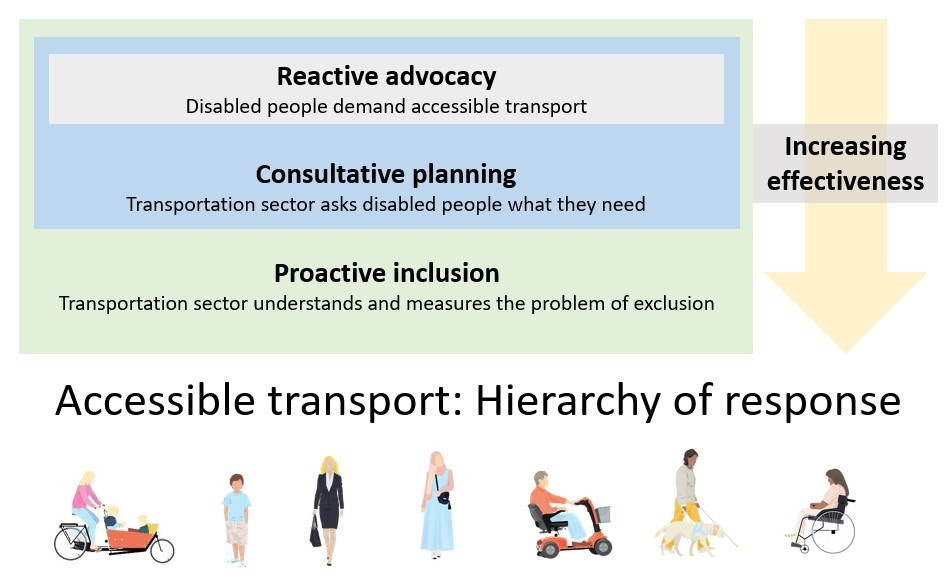

I think that there's a hierarchy of response. The options are presented here in order from most to least obvious, and least to most effective, in terms of their power to create real improvement in the universal accessibility of transport infrastructure and systems.

- Reactive advocacy

- Consultative planning

- Proactive inclusion

1. Reactive advocacy: Disabled people demand accessible transport

Sometimes the lack of accessibility is so obvious and illogical there is justified uproar from disabled people and their allies. One-off interventions happen thanks to complaints and law suits, driven by the seemingly tireless efforts of people who are otherwise excluded from living their lives with the same dignity that non-disabled people experience. The history of social change is grounded in grass-roots advocacy like this. And when the government or building owner sees the light and builds the ramp (or provides signage in braille, or fixes the wayfinding, or whatever) they pat themselves on the back and the fuss dies down for a while.

Reactive responses are necessary, and justified. But they only need to happen because we aren't mature enough as a society to do better. The money for these interventions is typically 'found' in a budget somewhere, so the hero investors feel that they've done something good simply by meeting their legal obligations to let people live.

2. Consultative planning: ask disabled people what they need

More mature and more effective is engagement with people with lived experience of disability, and their allies in professional practice. Many government departments in New Zealand have disability advisory groups of some kind. At best, these panels comprise paid experts from the disability sector. They advise on accessibility features for new infrastructure, and recommend audits or wider engagement for projects that are particularly important or challenging. Advisory groups and broader disability sector engagement are necessary because the transport profession is itself not diverse. Fewer than 2% of Engineering New Zealand's Transportation Group (of transport engineers and planners) identifies as disabled. The design codes that engineers and architects use can rarely be 'slapped on' to new development, because there's not enough space, or enough budget, or enough will. So advisory groups act as advocates within the system, pushing for best practice for the projects they are asked to review.

Like reactive advocacy, consultative planning can make decision makers feel that they are doing a good job on inclusion. Having (some) projects endorsed by an advisory group might feel like a job well done. However, the groups' very existence can limit the ability of government leaders to do better.

3. Proactive inclusion: the transport sector understands and measures the problem of exclusion

In proactive transport planning, we do not rely on a committee of commuters to tell us where to put a new traffic lane, or a forum of grieving families to provide advice on road safety. Instead, we use models, metrics and monitoring to continually improve our understanding of the interaction of transport and human behaviour. We set policy performance indicators (such as actual travel times and crash rates) and use their outputs to inform how much we invest, and where next to intervene. This level of policy maturity is entirely absent when it comes to accessible transport. We do not measure the frequency of trips not made due to access barriers, or of the time premium a disabled pedestrian accrues due to the lack of accessible footpaths and road crossings. We wait for them to get really angry about injustice and then pat ourselves on the back for fixing a pot hole or moving a rogue electric scooter out of the way.

Nowhere in the world does proactive inclusion in transport well. To do it requires two actions. First, we need to measure the failure of the transport system to provide accessible environments. That means counting trips not made at population level and (therefore) making exclusion explicit. This is possible as part of routine travel surveys: "in the last week, was there a trip you did not make because it would have been too hard?" The more data we have in response, the more we can understand patterns - who is most affected, by what problems - so that overarching budgets can be set. This is exactly what we do in road safety, mapping and analysing crashes at population level to understand the overall problem of road trauma.

The second action is to measure diversity of participation at street level. Just like we analyse crashes intersection by intersection to prioritise, if we know that one street has a high proportion of disabled people, and another does not, we can invest in upgrades according to objective, unmet need. Counting mobility aids is one (imperfect) way to measure diversity. In New Zealand approximately 1% of the population uses a wheelchair, for example. It we observe 5% of pedestrians using a wheelchair at an accessible shopping mall, and fewer than 0.5% on a city street, we can start to wonder why that is. The more data we collect, the more sophisticated we will be in understanding the travel demand of disabled people, and the contribution of accessibility barriers in their likelihood to appear on any specific street.

Proactive inclusion will always benefit from advocacy and consultation. But we will not see a step change in providing for disabled people until we measure more than traffic and crashes. Some people do not travel as much as they want or need to. That fundamental failure needs to be owned by the transport sector, and measured, if we truly want to create universally accessible transport infrastructure and systems.