Road pricing: a boost for Auckland’s transit?

Wed, September 15, 2021 | Public TransportThis post from Nicolas Reid, our Principal Public Transport Planner, was originally posted on LinkedIn.

The idea of a road pricing for Auckland was in the news last week as the select committee reported back on its inquiry into the Congestion Question report. In this post I’ve looked into how the Auckland public transport network might look like if road pricing was implemented and the revenue was used to boost alternatives to driving.

What is road pricing?

The basis of the road pricing concept is to charge a toll to drive at congested times and locations, effectively charging individuals for contributing to traffic congestion and the impacts their driving makes on other road users. The Congestion Question proposed a charge of $3.50 at the worst of the morning and evening rush hour, dropping to $1.50 on the shoulder peaks either side, with no charge during the middle of the day or across the evening and night.

The theory goes that without a price, people only make choices around driving based on their own costs of money and time. But with an appropriate price signal for congestion, the costs of money and time externalized to other road users becomes part of the equation. Some people might choose to drive at other times or locations instead of paying the levy, or they might decide to shift their travel to another mode such as public transport, walking or cycling, or in some cases they might just drop the trip entirely if it isn’t that important to them in the first place.

The proposed benefit of road pricing is freer-flowing roads. The mild traffic during school holidays shows that a small drop in driving demand can have a big improvement on traffic. The idea of road pricing is to make that periodic drop permanent, with modelling suggesting that a 5% reduction in driving trips will result in a 25% reduction in congestion delays. This should not only benefit the remaining car drivers, but also make things more reliable for freight, commercial vehicles and buses, and in theory less peak traffic should also make it at least a little nicer and safer to walk and ride on the streets too. So rather than road pricing it’s maybe better to describe it as a ‘decongestion charge’.

Issues and equity concerns

However, road pricing alone is not a silver bullet to fix everything. It doesn’t remove traffic congestion entirely, it doesn’t fix the street network for those on foot and bikes, and it doesn’t fix public transport. For anyone shifting to public transport, the speed and capacity gains for most buses would be marginal at best, while there would be no change for the busway, trains and ferries other than more crowding at peak times.

And of course, the greatest issue is equity. Few people drive in congestion if they can help it, they drive in peak traffic to get to work or study, or to manage their family or personal needs. Is it fair to penalize people for something if they can’t avoid it? There is a painful irony in the premise of all of this. We have spent decades reconfiguring our streets, our homes and our businesses around private road transport, to the point where most individuals have no viable option other than driving if they wish to hold down a job or engage in society. We then acknowledge that the congestion caused by all these individuals is bad for the economy and society, so we propose to charge the individual a fee for causing congestion!

But what about the revenue?

However, there is a subsequent factor at play: the revenue. Road pricing would generate a revenue stream that could be used to fix the alternatives and offset the equity issues. Indeed he select committee inquiry has identified the equity issues and the revenue as critical to the whole concept, and issued two recommendations that directly target these:

The Transport and Infrastructure Committee has conducted an inquiry into congestion pricing in Auckland and recommends that the Government… use any revenue raised by a congestion pricing scheme to: mitigate equity impacts, reinvest in public and active transport in the region where the charge applies use any revenue raised by a congestion pricing scheme to:

- mitigate equity impacts,

- reinvest in public and active transport in the region where the charge applies

This direction is clear, use the revenue to reinvest back into Auckland public and active transport and mitigate the equity impacts. So this lead me to think, what could that reinvestment look like? What would it gain us and how would that help?

What to do with Auckland's public transport?

Public transport in Auckland is like the proverbial Curate’s Egg, It looks bad in places but parts of it are indeed excellent. Before the temporary, hopefully, upheaval of Covid-19 public transport carried over half the workers and visitors headed to the city centre each day, including over 90% of motorized trips to the central universities. Buses carried almost half the people crossing the harbour bridge at peak hour, and if you add in the ferries the majority of peak commuters crossing the harbour did so on public transport. Where it works, it works well. Getting to central destinations is quick and easy by public transport, especially at peak times, and often already faster than crawling in traffic and paying for parking in town.

However the same does not hold true for every else around the Auckland region, if you’re travelling in the suburbs in off peak hours it’s a much different story. My colleagues recently published research into transport access and equity. In short, the report identifies the biggest thing for equity would be higher frequency of public transport in off-peak hours to make it realistic to use in all times and places. If you disregard the red herring title about free fares, this article outlines what is lacking with public transport. Just look at the quotes,:

- " unable to use public transport as her job is outside the normal 9 to 5 hours… one of an army of off-peak workers facing the same problem"

- "One of our sites, we wouldn't be able to rely on public transport because not once have I ever seen a bus"

- " people living on the North Shore are being forced to drive to get to the airport [but] we can't even get our residents in Papakura to work on time"

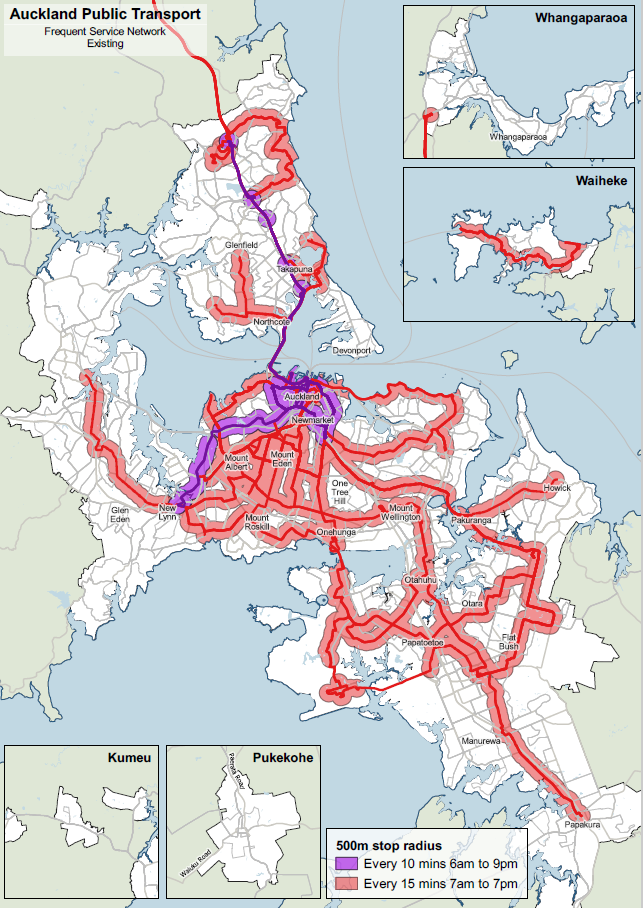

Now to be fair Auckland Transport has delivered some great improvements with the New Network and have delivered an all-day, every day frequent service network across large parts of the city. But it still has its limitations. You can see this in the map of the network below, here the red areas show the catchment of routes that run at least every 15 minutes from 7am to 7pm, seven days a week. That’s not bad, and better than many peer cities. But there are some clear gaps in the frequent network outside the central area, especially with none of the train lines or ferries meeting the 15-minute all day standard. Furthermore, a 15 minute wait is still on the edge of what you’d call ‘frequent’ transit, and infrequent service after 7pm limits a lot of people who don't follow the conventional commuter pattern.

The purple lines below show the extent of the network that really meets a true ‘turn up and go at just about any time’ standard. These are the routes that run at least every 10 minutes from 6am to 9pm seven days a week. These are basically just the two Link buses in the city centre, the main route of the northern busway, and the No.18 bus on Great North Road.

If public transport is going to mitigate the effects of road pricing, it needs to work well right across Auckland, for a lot more Aucklanders. So I’ve taken this as the primary focus of this experiment: what if we spent some of the road pricing revenue boosting the frequency and hours of operation on the Auckland transit network, what would that look like?

The potential budget for transit upgrades

So let’s lay out the budget we could get from road pricing. In roundabout terms, stage two of the road pricing scheme proposed for the Auckland isthmus and North Shore would generate $250m a year in levies. Less the $50m cost of running the system, this would leave $200m a year in in net revenue. For arguments sake, lets split that fifty-fifty between infrastructure and operations. Allocating half of that annual revenue to active and public transport infrastructure would sustain a one-off capital programme of around $2.5 billion. The best way to spend that is whole other story, but it would easily deliver a world class region-wide walking and cycling network, and have money left over for a big package of bus stop upgrades, transfer stations and the like.

So assuming the other half of the budget means a $100m annual boost to public transport operations. What would that buy us? I won’t bore you further with the calculations of boardings per mode, cost rates, farebox recovery ratios, subsidy per service-km etc. (DM me if you are actually interested in this stuff!), but long story short $100m a year extra subsidy would allow Auckland to run 38% more bus, train and ferry services.

That doesn’t sound like a lot, but it’s all at the margin where the gains for service frequency and span are very significant. The fact is we do have at least some kind of public transport serving just about every part of the city, so in a lot of cases you can run peak service levels for longer or extend service hours for relatively little extra cost, and get better utilization from the existing fleet and resources.

Q: What would an extra $100m a year do for public transport operations?

A: A hell of a lot!

To test this, I built a model of all the transit lines in Auckland using data from the Auckland GTFS data feed, which is the system that online journey planners like Google Maps use. This feed includes the full timetable every single bus, train and ferry route, including the run times and route distances, so it can be used to calculate the frequency of every line at each hour of the day and day of the week, and the resulting service kilometres, hours and fleet sizes for the whole network. This model allows me to change frequencies and spans of any route on the network and see the corresponding cost to the overall budget.

I used this model to test the cost of adding service frequency to a range of existing routes. Effectively I worked my way through the network line by line, adding service frequency to promote routes to 15 or 10 minute all-day headways, and to widen the span of this frequent service to a minimum of 6am to 9pm. Where routes already ran better than this frequency at any time I left it at the higher level, and likewise all routes continue to operate to the current timetable before 6am and after 9pm. For this exercise I added the extra budget in proportion to the current service levels, so that each mode and area got about the same relative increase. However, I didn’t modify any routings or add in any routes, so it’s probably not as optimized as it could be, and I’ve left some things unchanged where infrastructure problems would prevent major changes.

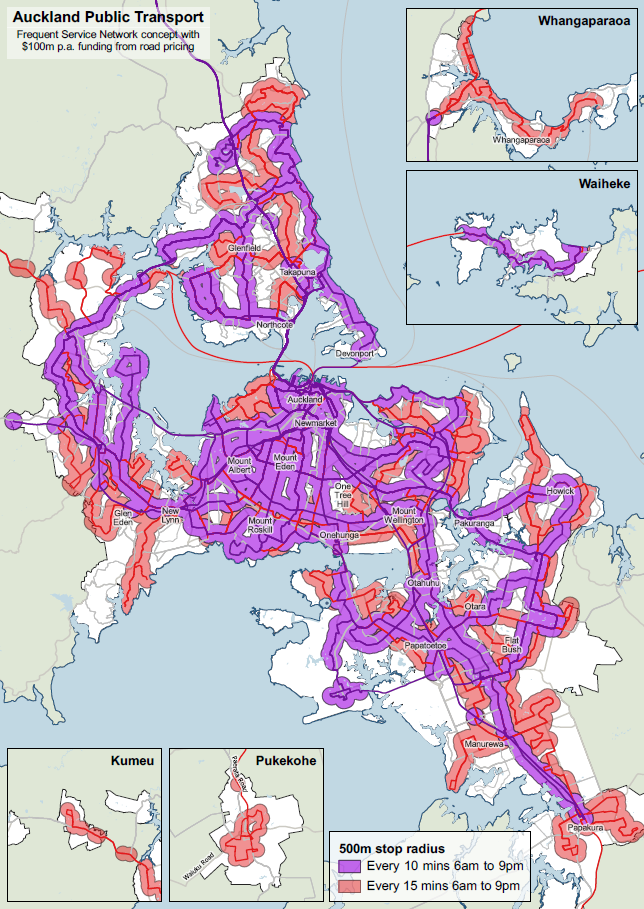

I expected good results from this exercise but was frankly astounded at just how far the extra funding could go. The map probably explains it the best, this shows the network with extra funding, in this version the purple lines are all at least every ten minutes from 6am to 9pm seven days a week, and the red lines are at least every fifteen minutes, but also from 6am to 9pm every day. Now I don’t claim to have this perfect around exactly what routes should get upgraded, but it does show you that sheer extend of what public transport could achieve with a relatively small increase in operations funding.

To summarise, that funding boost from road pricing would be enough to get:

- Just about every main radial and crosstown bus route on the North Shore, West Auckland, the central isthmus and across South and East Auckland running every ten minutes all day, every day, on a network linking every major suburb, shopping centre, employment zone in the region.

- Most collector bus routes operating frequent service every fifteen minutes all day to local suburbs and residential areas in between.

- The Eastern, Western and Southern rail lines running at least every ten minutes from 6am to 9am, both ways, seven days a week, with the Pukekohe branch running every fifteen minutes.

- The Devonport ferry departing every ten minutes all day, both ways, and the Waiheke and Hobsonville-Beach Haven ferries every fifteen minutes.

- Both patterns of the northern busway running at least every ten minutes until 9pm, on the full route to Hibiscus Coast, plus the equivalent bus route on the Northwestern Motorway to Westgate doing the same.

- Local feeder buses covering Orewa, Whangaparaoa, Kumeu, Whenuapai, Papakura, Pukekohe, Devonport and Waiheke running every ten or fifteen minutes until 9pm every day, connecting to these main train, busway and ferry lines.

The outcome in numbers

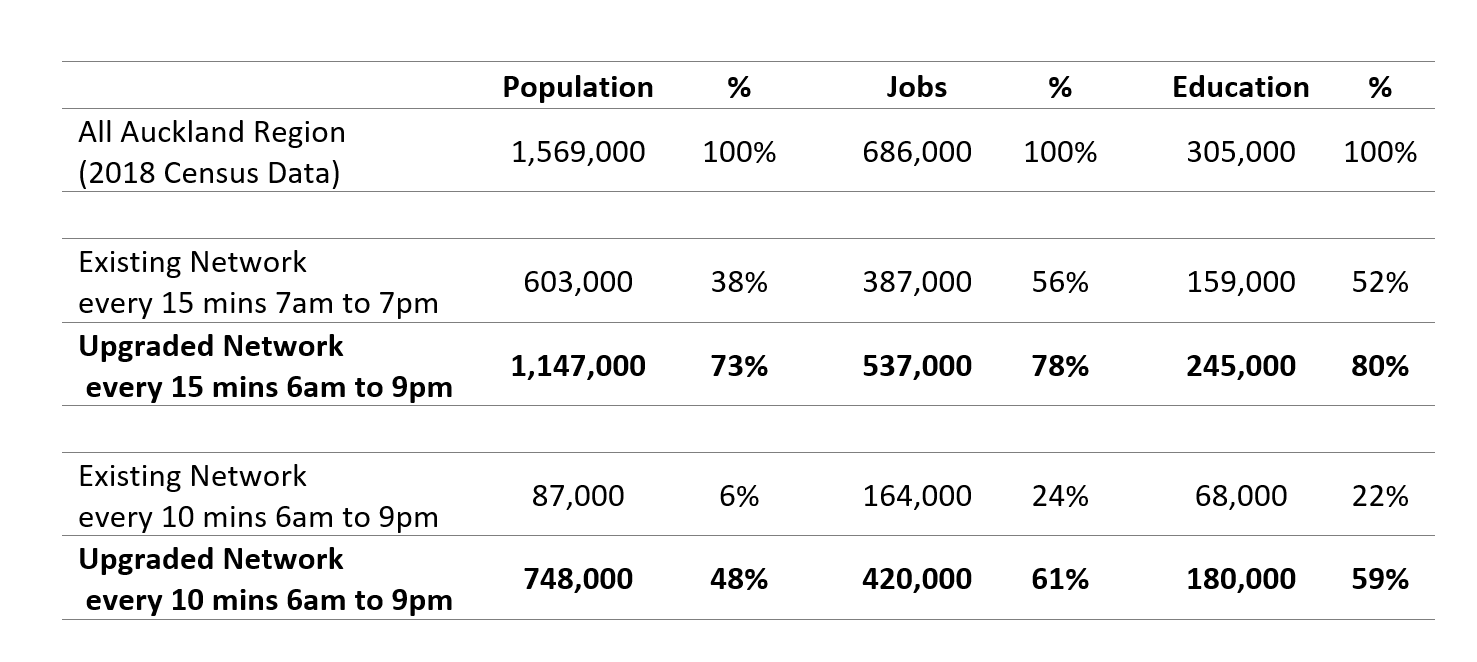

To quantify the effect of all these service upgrades, I crunched the catchments in GIS using census data on where people live, work and study in the Auckland region. Overall, this would mean three-quarters of the Auckland’s residents and 80% of jobs and education places would be within 500m of a bus stop, train station or ferry wharf served by routes running at least once every 10 to 15 minutes from 6am to 9pm, seven days a week.

Conclusion (TL:DR just skip to the end)

Spending half the annual revenue from the proposed road pricing scheme on public transport operations would upgrade Auckland’s bus, train and ferry network to a comprehensive connected system with turn-up-and-go services running frequently through practically every neighborhood in the region, from early morning to late evening, seven days a week. This would easily give Auckland the best ‘all day every day’ transit network in Australasia and go a long way to dealing with the equity issues of road pricing.